Introduction

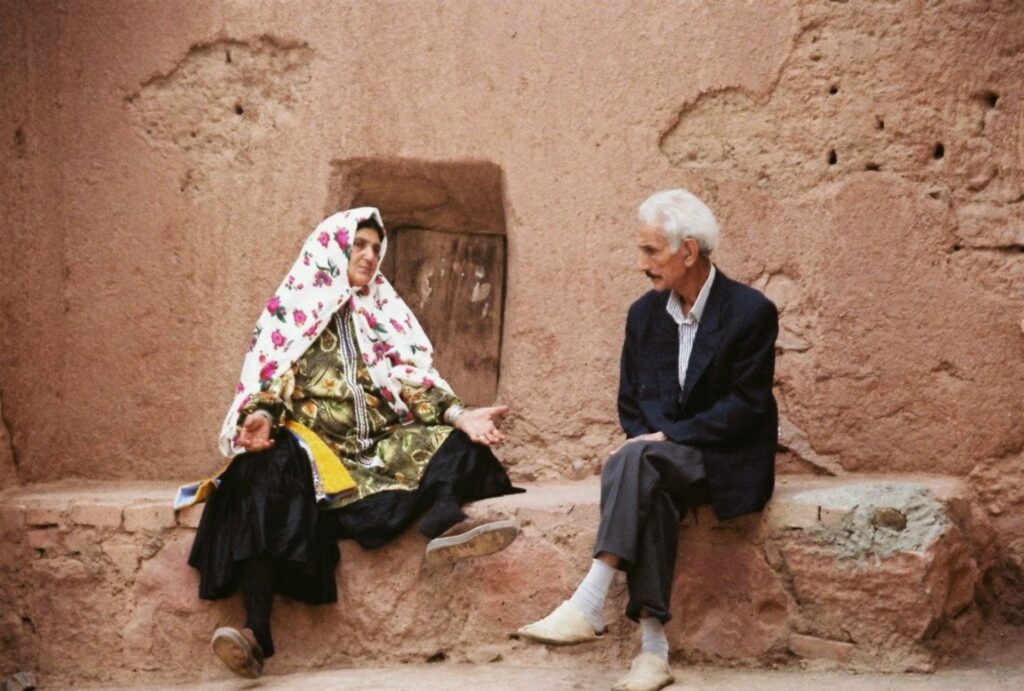

The term “elderly” refers to individuals who are aged, old, and long-lived, defined as a person in the final stage of their life cycle. Generally, the age of 65 is considered the threshold for entering old age, although it may vary based on individual physical conditions. The elderly population faces a decline in their overall well-being and physical health, making them susceptible to a range of illnesses, discomfort, and emotional and mental challenges. They need special attention and necessary care from their relatives at this juncture, and the government and relevant institutions should provide them with the necessary support, including essential facilities and optimal conditions. According to the head of the Secretariat National Council of The Elderly, there were approximately 9.2 million elderly individuals living in Iran in 2022.[1]

Elderly individuals are among the most vulnerable populations, and economic and livelihood crises, along with shortages of essential goods and medication, can greatly impede their quality of life. The imposition of comprehensive and seemingly targeted international and unilateral sanctions against a state exacerbates such crises. In fact, the main victims of these sanctions are ordinary people, especially vulnerable groups such as the elderly. Currently, the impact of sanctions on vulnerable populations is a clear and evident example. This text will briefly outline the two primary dimensions of the sanctions’ impact: the right to health and living conditions.

Right to Health: Access to Medicine and Medical Care

Compliance with sanctions by states, as well as private actors, is based on considerations including the risk of punishment and fines due to commercial transactions with Iran. This compliance even extends to humanitarian deals and basic goods, such as medicine. In Iran, sanctions have also affected the availability of medicines and medical equipment, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In recent years, Iranian NGOs have addressed the effects of sanctions on the right to health of Iranians and vulnerable populations during sessions of the Human Rights Council, either in the form of statements or by holding sittings.[2] Also, the Special Rapporteur of the Human Rights Council in the field of unilateral coercive measures confirmed the destructive role of sanctions in this crisis in the 2022 report.[3] Sanctions on medicines and medical equipment result in shortages, price surges in the market, and the proliferation of illegal economic activities and profiteering.

As mentioned, the elderly population is at an age of physical weakness and is exposed to various diseases; this group is the most in need of medication to treat diseases and compensate for disabilities. The elderly face medical problems and illnesses such as Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, heart disease, stroke, and Parkinson’s disease; these medications are crucial for the elderly individuals involved.

Available reports show a lack of medicines for these illnesses. For example, medicines for cancer patients, who are elderly individuals at risk of this disease, have been declared scarce, and the cost of providing them has also been deemed expensive.[4] Additionally, there have been numerous reports regarding the scarcity of the essential and irreplaceable medication “Warfarin” for patients with heart conditions.[5] It is important to note that heart disease is among the most prevalent ailments affecting the elderly population.

In the field of medical facilities and healthcare, there have been significant shortages due to sanctions. This issue was particularly severe during the COVID-19 pandemic. Iran experienced a shortage of test kits, respiratory equipment, and other essential medical supplies in hospitals during this period.[6] The elderly population was considered one of the most vulnerable groups to the coronavirus, and the lack of these facilities had a direct impact on their suffering and mortality rates. Furthermore, in the post-pandemic era, the scarcity of these medical items (such as respiratory equipment and oxygen), along with the high cost associated with providing them for elderly individuals with common diseases at this stage of their lives, leads to numerous challenges for this group.

Livelihood and Economic Circumstances

Experimental research in Tehran in 2022 reflects the existing kind of “Multidimensional Poverty” among the Iranian elderly. The concept of multidimensional poverty refers to the existence of poverty that goes beyond assessing individuals solely based on their financial and material possessions. It includes aspects such as treatment poverty, health poverty, and social life poverty. This term is an index for measuring poverty in different dimensions, including the mentioned aspects.[7] According to that research, the Iranian elderly face challenges in meeting their economic needs and employment. Investigations reflect that old people who were employed in public service and are now retired, due to social security and retirement programs, have better material conditions than those who had private jobs and do not have income or savings for their future during old age.[8] The difficulty of trade exchanges with Iran and the constraints on Iran’s economic connections due to unilateral sanctions imposed by the US have resulted in economic crises and welfare issues. This has led to an escalation in the prices of essential commodities and the overall cost of living for Iranians, directly influenced by these unilateral measures.

Results of investigations affirm that the downturn and economic crisis, which were a result of sanctions, have seriously influenced the Iranian welfare and elderly population who are not retired from public service and do not have noteworthy support from social security, so they have been harmed more.[9] Some groups of elderly people are unable to work due to illness and disability, relying on their family and relatives for income. However, the special salary of elderly people who are retired from public service or had private jobs but enjoy social security benefits may not be enough due to rising prices and the cost of their medical and care needs.

Some public retirees have also resorted to freelance jobs in order to supplement their living expenses. However, old age should be a period of comfort and well-being for this demographic, and these individuals should be free from the challenges and psychological pressures associated with freelance work and concerns about meeting their needs.

Assessment

The elderly, as a vulnerable group, should be supported. However, the past international and current unilateral sanctions that have targeted Iran’s economy and hampered humanitarian exchanges with Iran have severely affected this group. Their right to life and right to health, along with their social and economic rights, have been violated as a result of these sanctions, and these sanctions have had destructive effects on their social security. Therefore, international assemblies should firmly condemn the imposition of these sanctions and take more effective steps to stop such actions against the vulnerable sections of Iran and even other parts of the world.

[1]. “There are 9.2 million elderly individuals residing in Iran”, Irna, 2 December 2023, accessed 21 July 2024:

[2]. For example, the statement of Pars Development Activities in The 51st session of the Human Rights Council (September 2022), accessed 21 July 2024:

https://humanrights.eadl.ir/news/articleType/ArticleView/articleId/107898. (In Persian)

Also, the panel on the impact of sanctions on the right to health by several Iranian NGOs at the 52nd session of the Human Rights Council (March 2023), accessed 21 July 2024:

https://humanrights.eadl.ir/news/articleType/ArticleView/articleId/109049. (In Persian)

[3]. Human Rights Council, ‘Visit to the Islamic Republic of Iran: Report of the Special Rapporteur on the negative impact of unilateral coercive measures on the enjoyment of human rights, Alena Douhan’ (4 October 2022) UN Doc A/HRC/51/33/Add.1.

[4]. Report of Asr Iran, 20 May 2024, accessed 21 July 2024:

[5]. Report of Fararu, 5 May 2024, accessed 21 July 2024:

[6]. Rahbar Taleihur and Zahra Mobini, “The Impact of US Economic Sanctions on the Health Security of the Islamic Republic of Iran in the Corona”, American Strategic Studies 2, 2 (2022): 110-111. (In Persian)

[7]. See, “Multidimensional Poverty Measure”, World Bank, April 2024, accessed 22 July 2024:

[8]. Ilyar Heydari Barardehi, Mahnoush Abdollah Milani and Sepideh Soltani, “Economic Sanctions and the Material Well-being of Iranian Older Adults: Do Pensions Make a Difference?”, Social Policy and Society (2024): 4-5.

[9]. Ibid., 10-11.